by Benedikt Eiden

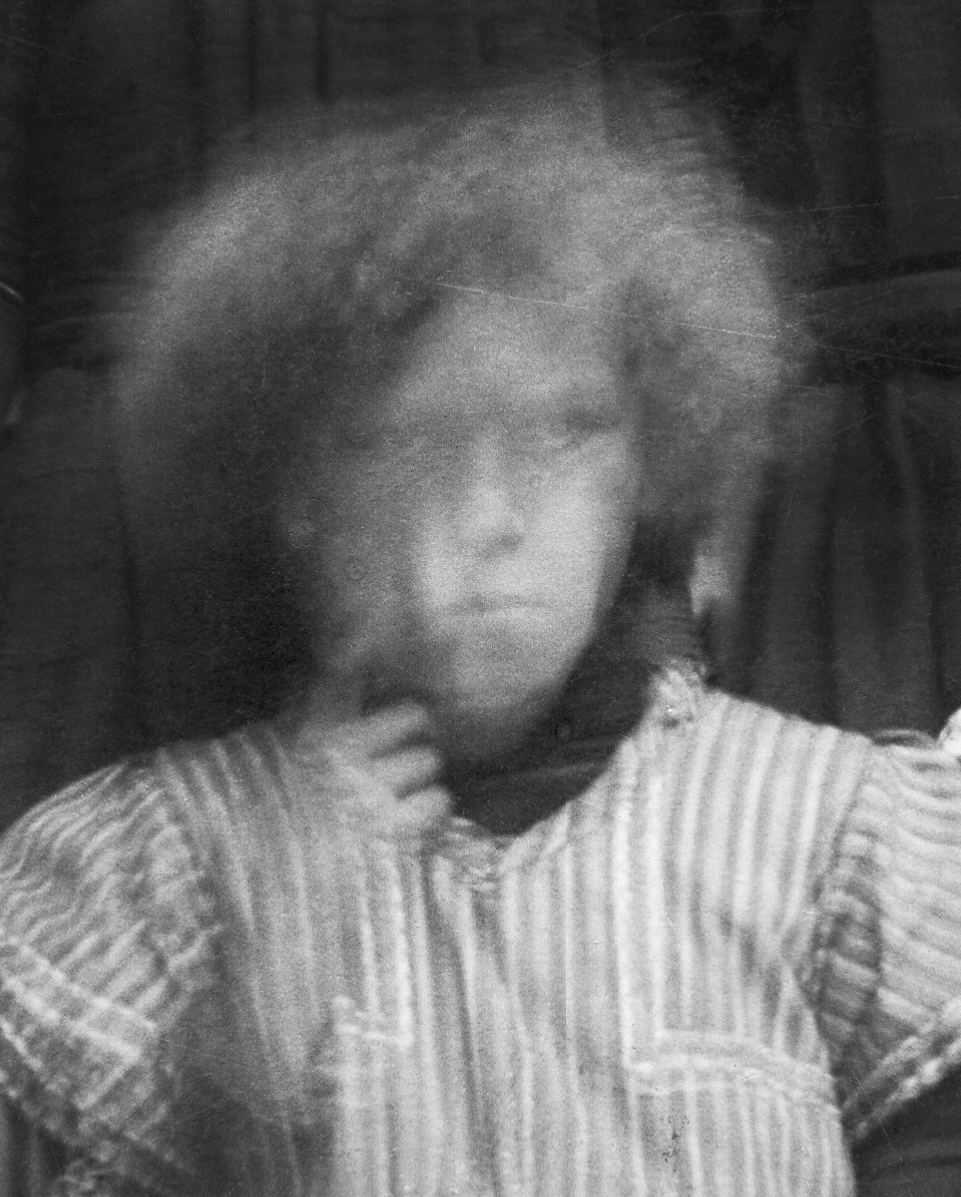

A worn cardboard box, grey and stained, on the back is written: Photographische Anstalt, Steinach. On the front is a class photo. On both sides are the teachers, dressed in strict uniform: three-piece suit, remarkably high stand-up collar and, as was still fashionable well into the 1920s, the chain piece of the pocket watch peeping out of the waistcoat. In addition, a protruding moustache and steel-framed glasses. In the middle we see the miserable-looking, strangely undisttinguishable faces of the children. In one of the lower rows, almost exactly in the golden section, stands a girl who apparently could not wait for the exposure time to end. With a peculiarly serious expression, her index finger raised as if to convey a mysterious message, she looks straight past the camera through her ghostly blurred doubling.

What journey must the photo have taken by the time it ended up in a junk shop in Berlin a whole century later and is pulled by me from one of its crammed back rooms? A relative might have kept it – for decades it must have been in some drawer among old linen and table runners, embedded in the heavy smell of mothballs and lost liquorice. After some time, also this life, along with the class photo, apparently ended slightly irreverently here in a red plastic tub. No one would remember the names, not even the faces – almost as if their lives had been subsequently erased. My glance falls again on the grey cardboard, on the only child of the class who wouldn’t hold still during the up-to-half-minute-long exposure time of the large format camera. I am a bit astonished – the photo I’ve just found suddenly seems more mysterious, somehow more obscure than its concreteness would suggest.

In the same way the girl seems to vanish from the photograph, she also seems to want to vanish from any memory, I suddenly think to myself. As the only guest around, I silently step out of the musty back room again. The shopkeeper stands up front at the counter in the pale light of the ceiling lamp and subtly observes my doings.

In her essay On Photography, Susan Sontag says at one point that the Surrealists’ fascination with flea markets and antique fairs contributed to turning a visit to junk stores into what came to be perceived as an “aesthetic pilgrimage”. This quote may be true for those whose visit is more casual or accidental – a teapot here, a cup there, a seven-inch here, a side table there –, but if one spends more time than necessary in the shadowy realm of the mundane and the scattered, in this seemingly never-ending stream of discarded photographic material, the “pilgrimage” becomes, it seems to me, a somewhat questionable undertaking. In a way, it may feel like crossing into a sphere of the private that would have otherwise most likely been kept under lock and key. Every now and then, also a certain bleakness creeps upon the viewer when at the sight of dizzyingly identical interiors or stiff nude photographs, suddenly the futility of existence becomes palpable. (Sometimes, moreover, it seems as if the same faces recur in different places, as if they were all one large family of ghosts). If one considers all of this with some care, free of cynicism, then each of these photographs eventually becomes connected with a wealth of stories and memories – memories that meant a lot, or perhaps hardly anything at all. Memories that, as cultural scientist Aleida Assmann describes in Erinnerungsräume, all “undergo a metamorphosis when they emerge from the context of living actuality”. These memories have thus lost not only their context but also their function: cut off from their source, they continue to exist in obscurity as silent references to a life possibly lived, becoming contextless objects – a product of waste.

Nevertheless: among these photographic memories which, when taken out of context, become nothing more than junk or garbage, smaller gems emerge from time to time that need to be preserved. Photographs that, whether due to overexposure, blurriness, odd perspectives or signs of age such as fading and corroding, sometimes can appear unsettling to the viewer. (The veiled face of the girl or the man sitting in the mist on the cliffs somehow stayed in my mind, caught my attention.) Leaving aside their aesthetically pleasing characteristics, most of these images accumulated over the years are probably not major discoveries or revelations: most of them are unassuming raw slices of the world which, through their randomness, it seems to me, become able to trace real life all the more precisely. Among them are hundreds upon hundreds of photographs of being on the road: of excursions and journeys to Hiddensee and the Thuringian Forest, to Burgenland or the Alps, to Italy and the Tyrrhenian Sea. They tell of faded summers and of all kinds of cheerfulness, of the “I’ll-just-go-along-with-it” attitude and the expectant, sometimes questioning look at the lens. They tell of everyday rituals, of quasi-sacred places like the living room, the kitchen, the forest – of a supposedly well-ordered, respectable time. It was only later, while sifting through them, that I noticed that many of the photos date from the time span between the post-war period and 1970s, and more likely belong to the German petit-bourgeois milieu. Impressions such as a large-bloomed Sunday dress or a perm helmet, like baroque wallpaper or monstrous, walnut-wood wardrobes, are also fleetingly familiar from my childhood. And yet, for all the tranquillity that many of these pictures give off, it is as if behind the visible reality, behind the bourgeois façade, already lurks another order of things – as if a sinister certainty were already inscribed in them from the moment they were taken. Admittedly, all these images, like memories, can only ever represent fragments of a life, can only convey an idea of the circumstances. On the other hand, though their ability to document that other reality, the transience (that “inventory of the mortal”, as Susan Sontag puts it) seems all the more real. It can be said that this inevitably slightly uncanny characteristic of photography, mirrored in those nostalgic bourgeois impressions, always exerted a dull fascination on me, which, after years of sometimes casual, sometimes active collecting, eventually resulted in this work.

If this book can therefore ever achieve any kind of memory work beyond a purely artistic one, it may be that of a last gallery of the systematically overlooked and seemingly indifferent beyond the cultural storages or photo archives. If you like, more dream than memory work, because what remains – tangible and plastic – is the physical memento: institutional places of remembrance, memorials and monuments, all of which are equipped with specific functions when it comes to the persistence of perception, consciousness and knowledge – contrary to a collective repression.So why this small collection of the culturally insignificant? Why the urge to want to remember and hold on to it? Can’t freeing oneself from the weight of a biography and forgetting memories be just as beneficial to the soul of an individual? On the way into the depths of a past where the unspeakable is simmering, where guilt and trauma, perhaps even humiliation, persecution and the like are to be found, some memories would surely want to be repressed or erased. It seems as if the pain is inevitably connected with the process of remembering (which is perhaps even necessary to become aware of oneself again). But this is not about securing traces of traumatic engrams. This compendium is intended to set in where oblivion has long since raged: a silent collection of scattered relics, a last stop before – this much sentimentality is allowed – the contours of life are completely blurred as if nothing of permanence and meaningfulness had ever existed. Lethe, that mythical river of the Greek underworld, river of forgetfulness and transience, it is said, then brings salvation to the departed souls in its shadowy realm: if one drinks from its waters, all knowledge, all experience, all the burden of earthly memory will dissolve and evaporate. In John Milton’s verse colossus Paradise Lost, this is described as follows: “Far off […] a slow and silent stream, Lethe, the river of oblivion, rolls/Her watery labyrinth, wherof who drinks/Forthwith his former state and being forgets. Forgets both joy and grief, pleasure and pain.”

A colour photo. Found in a chest of drawers in my parents’ living room. The view leads through a kitchen window straight onto a flat meadow. It’s a bit unkempt and still undeveloped, with a few sorrel flowers blooming. To the left is a small crossroad, on it a car that seems to be tipping over to the right. Behind it are two single-family houses, surrounded by rows of black-green fir trees; in the distance one can already make out the hilly West German landscape. The photo is surrounded by the blurred outlines of the curtains forming a vignette; two fire-coloured glass balls are also out of the camera’s focal plane, and seem to float extraterrestrially in front of the window. On the back it says: July, 91. My eyes still linger on the photo for a while. Then I begin to feel the weight of the pale sky, notice the silence of the surrounding houses, already hear the pleasantly sedating hum of the autobahn in the valley, see the huge magpie in the birdhouse. I try to think of something else. Of tomorrow’s trip. Of my flat, of the big city. Of its streets with their seemingly endless hem of rubbish and other things that have fallen out of the cycle of usefulness, of the lonely screamers wandering through the night, of people on pavements staring into the most immediate present, day in, day out, while all around life takes its firm course. I think of the flickering, unpredictable feel of the first years in this place. Of those immanent thoughts of failure, of compulsive self-accusation, of the senseless mental exhaustion of the last weeks and months. Of the fact that freedom grew out of blankness. The fact that the latter gradually took on a meaning in which I could permanently find myself again. I put the photo back in the small box, stow it deep in the living room dresser. Nowadays when I arrive at this place, familiar to me down to the smallest detail, I am sometimes not quite sure what makes me leave it again with a sense of melancholy. Certainly, it is the place where I grew up and which therefore represents a kind of memory for me. A place where things begin to speak by themselves, where everything lies clearly in the air. Where that air still smells heavy and sweet. Where there is no manic hustle and bustle, no pissed-off general tone, where a few elderly people in quilted jackets go their way and the same young people as twenty years ago sit on the benches in front of the station kiosk.

The next morning I was back on the platform again; around noon I would arrive in the city. Lost in thought, I was watching my breath rise steamingly into the cold air. Won’t all this, all the family possessions passed down over the decades, perhaps centuries, all the images of a past, everything that means so much to me and at the same time perhaps nothing at all, won’t all this too end up in a box at some flea market or directly in the rubbish in the foreseeable future? Will home become a place that is lost the more I want to hold on to it? Perhaps this book is meant to counteract that unbearable thought of the fleetingness of existence, that persisting sense of alienation. Perhaps these feelings and that interest should not be expressed directly in the personal, but, out of reasonableness, through a selection of the accumulated images. Because after all, aren’t they generally the same experiences, the same emptiness, the same ceaseless effort and maintenance, the same summer sun, the same laughter, the same optimism, the same fragile idyll? Somewhere it is captured in the images. Fragmentary and incomplete. And the rest can remain locked away and is moreover part of a communicative memory that, with its individual stories and narratives, is anyway much more formless and short-lived.

Outside the train window, a country road now began to run parallel to us. The shadow of the wagon trembled in frantic movements on the concrete. In the background, the sandstone cliffs glowed from the low autumn sun, and in front of them were a few villages and small towns of the southwest Palatinate, embedded in pale green meadows and still standing time. Identical shopping malls became smaller inns, which in turn became ramshackle half-timbered buildings and farmhouses, standing along the road like fossil remains. Through my half-opened eyelids, the sunbeams now flashed, dust molecules floated in the light. In some sort of twilight state, with my head leaning against the window pane, I was listening to the peculiar singing of Robbie Basho in “Moving Up A’Ways”. Then I dreamt I had walked through a rugged landscape. The path led over intersections of gravel paths along crystalline bodies of rock into a greenish shimmering grey. Walking through the steadily thickening fog seemed strangely effortless and time-lapsed, and I could still make out the trunks of a few trees, dull and seemingly transparent they were standing along the path. Further and further I moved into the vertical grey, which, as I knew in my dream, was the Hunsrück. And although I felt a bit enraptured, I remember that I was more at ease than I had been in a long time. The high forest, lying in a great haze, suddenly gave the appearance of a precious, airy, wide-branched lake. Everything was still and submerged, suddenly seeming entranced into indefinite distance. How far must one go back to the earliest memories and imprints? Along the fault lines of the past, past all the insignificant and scattered, past all dreams and longings, all the whirling images and archaic impulses. There, where the memory begins. Was there still a landscape that I was rooted in? I had probably just forgotten it. In this process of time spreading out randomly in all directions, in that course of things, somewhere drifting between the irrepressible life and its fleetingness, it would from now on be enough if I stuck to what was in front of me, what I could really grasp. As the diffuse orange glow of the big city was already ahead of us, I knew I would find this place again and again.

—

Originally published as the epilogue to Nektar & Lethe photobook by Benedikt Eiden