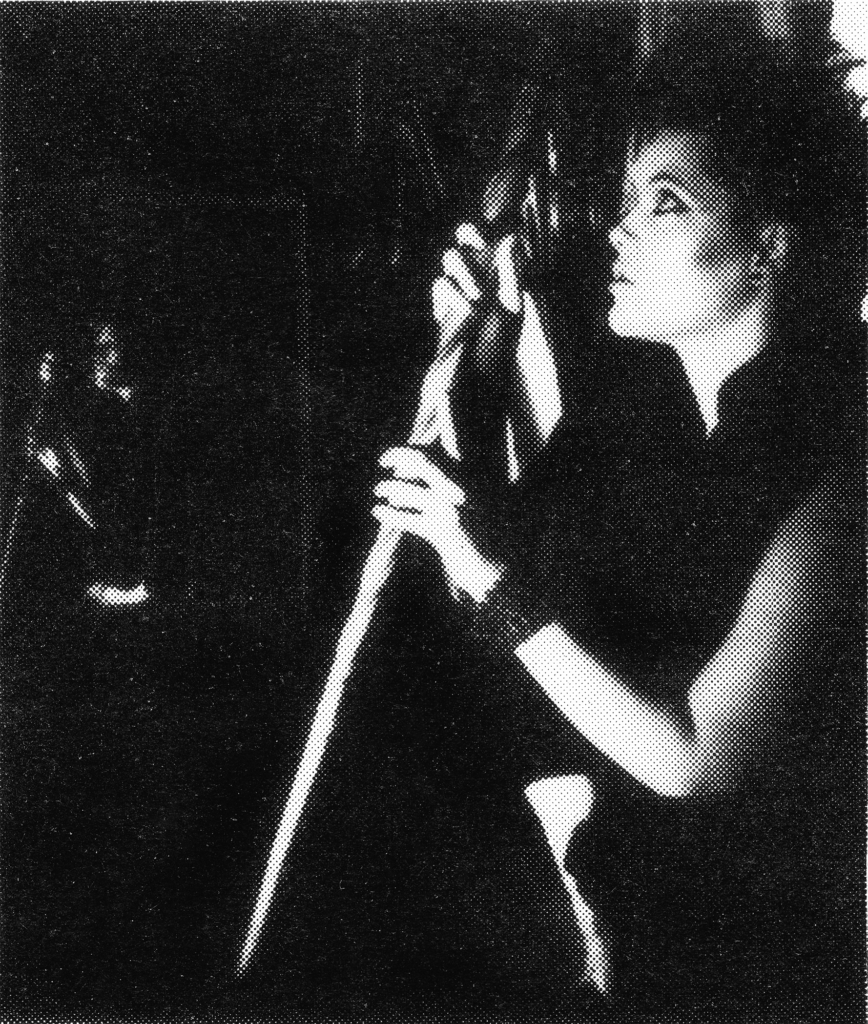

I was alone in the road of dreams enough as it is / And then you came along and then you came into my street. These were the opening lines of the song “Leo” and also one of the first lines I heard from Jeanette Dwyer. And something, along with its lush, wistful synth line, immediately pulled me down into the song, without being able to say exactly what it was. There was a power, an idiosyncratic beauty. As if something seductively unique, something still unknown to me, pushed out of the arty yet unadorned language, the soaring up-tempo rhythms, the slightly husky yet crystalline voice. I didn’t catch every word right away, partly because of the odd phonetics and the distinctly British accent, but the song seemed to be about the memory of a faded childhood friendship. We may be far apart but never far away […] And I’d look into your baby blue eyes, yeah ever since I never let it go. It was as if these lines wanted to linger in that nostalgic state where childhood impressions echo and the shenanigans of those days still ring in one’s ears. It’s hard to explain, the wise ones argue as we snuggle in the rain / And we got to sorting out the things that claim the parents, we saw beginning of the age. At the same time, these words seemingly wanted to free themselves from invisible conventions, from the past – if such a thing is possible. And I know you leave some time to wander, but that’s okay the mainstream never comes again. Here was an old, simmering pain, expressed with such elegance and profound honesty that I could not say whether I had heard anything like it before. “Leo”, I would argue today, is one of the most beautiful songs ever written about the way the wonder of childhood fades. But why is it, I keep asking myself, that hardly anyone seems to have ever heard of Jeanette Dwyer? Who was this singer from London anyway?

I first came across her a few years ago via the quasi-legendary YouTube channel of Scottish music archaeologist and DJ Fergus Clark. It was the eponymous track from her 1984 album Hum. At first glance, the monochrome album cover looked like one of the countless obscure wave records of the era, but the music – an a cappella piece with minimal electronic instrumentation – conveyed something far more light-hearted. It felt warm and playful, occasionally naive – certainly more intriguing than I would have expected from the cover. Throughout this snappy 30-minute album, Jeanette’s singing, especially in the higher registers, echoed the eccentric flourishes of Kate Bush, though embedded in a DIY aesthetic that was less elaborately produced, less concerned with grand gestures and more approachable in its inevitable simplicity. You could also hear an admiration for soul and jazz singers in her voice, for Dionne Warwick and Billie Holiday. It had a low-lit coolness to it, a rough edge that probably had seen many a sunrise over the city. Could this be the reason why Jeanette’s music made little impact in the indie scene, because even then she seemed out of touch with the zeitgeist and her style, the swing and cadence of her voice, was ultimately leaning more towards the 1950s and 60s, towards jazz and Brill Building? Relying on a sound that was already considered old-fashioned to cope with the present? You almost get the impression that her music never really fit in anywhere. Nonetheless, it was a oddly fascinating aesthetic that blended effortlessly with the subtle use of electronics. One that, much like the nocturnal love songs of Scottish pop group The Blue Nile, seemed imbued with the icy breath of the anonymity of the big city. With lyrics that told of lonely, aimless strolls in seemingly familiar surroundings – preferably in autumn, of course. Like a fool, steppin out in Autumn / Winds come too soon, feel I’m missing something / Leaves blowin around, like my dream they end up trampled on the ground, proclaims the elegantly desperate Hum album closer, “Like A Fool.”

In 1981, Jeanette responded to a search for a vocalist for a band called Analysis, which is how she first came to the attention of co-founder David Rome (the same Analysis that would soon become Oppenheimer Analysis and land the dancefloor classic “Devil’s Dancers”). Her voice must have struck him immediately. For just one year later, Rome released Jeanette’s first single, the simple, catchy “In The Morning” on his newly formed Survival Records. By this time Jeanette was moving in South London circles, around the aforementioned label and members of the New Romantic group Furniture, who were helping her with fleshing out ideas, with composing and producing. She was probably doing what many do in their early twenties: staying out late, ripping cigarettes, drifting through bars, all the while full of impulsive, creative energy, always “carrying around a carrier bag of booklets and tapes,” as Survival’s then layout designer Jim Irvin remembers. When talking to her former bandmates and producers today, nobody knows who Jeanette really was, let alone what happened to her. The remaining contemporary witnesses I contacted either didn’t want to talk or had little information, saying they “heard nothing from her in over 30 years.” Of course, I would have liked to ask her some questions. But then, about what exactly? What is the basis of this search? What is its core? Maybe it’s just the fragments, the gaps, that have such a magnetic effect on me: What happened after her last album in 1990? What artistic expression did she find in the years that followed? Why did she withdraw from music so radically? You’d want to tell this story from the beginning – the world she lived in, the circumstances of the time, all the interrelated details and distortions. “London voice Jeanette Dwyer is proof that it is still possible to disappear,” writes music journalist Martin Ashton in one of the few articles about her in the March 2017 issue of Mojo, in the “Buried Treasures” section featuring her 1988 album Prefab In The Sun. Because even he failed to track her down. A thorough search of the internet reveals only a few clues: scattered brief reviews in the NME from the mid-1980s and the aforementioned Mojo article. Even several – admittedly questionable – deep dives into Facebook, old social media archives and public registers in the UK failed to turn up any further clues as to her possible whereabouts (personal privacy shall be respected, of course). Perhaps some hints could be found in the YouTube comment sections of the songs uploaded by private users over the years (an upload of her single “Leo” – where, bizarrely, she’s mislabeled as “Jeanette Landray”– has nearly 19,000 views as of 2025). You come across a comment from twelve years ago, apparently from an old friend: “Jeanette!!! […] Been looking for you for years. Are you still in London? Last I heard you were in Gypsy Hill but had no luck in finding you. Would love to see you again.” But that, too, turns out to be a dead end. The traces Jeanette Dwyer has left outside her music thus seem so light that a breeze could erase them. One gets the impression that after her musical career quietly faded away in the early nineties, she radically retreated into a private life, perhaps not wanting to be found.

The language of an artist is, of course, inconceivable without their biography. It is the existential basis of their work, of its amplitude. But what kind of biography are we actually talking about here? As mentioned, there is hardly anything left to remind us of her today; little has survived beyond her music. Perhaps it is possible to construct something like a life story on the basis of what has endured. After all, her lyrics offer a glimpse of something like language as a place of escape and longing – words that hold firm, that offer orientation. In songs such as “Leo,” “Woman’s Love,” “Dear Daddy,” or the spellbinding “Twilight Playground,” individual experiences rooted in childhood memories, lost loves and encapsulated wounds emerge as powerful self-affirmations – painstaking attempts to free oneself, to arrive at one’s own self, at one’s own language. For the world seems grey and chaotic, yet full of possibilities. Presumably growing up in post-war London in the early 1960s, Jeanette spends her time on dirty bomb sites, on barren streets where love may never come again. She seems to have come of age in a poorer part of London, amidst the sphere of the slums. In South and East London in particular, war damage was still visible well into the sixties. Many houses, street blocks and public buildings remained in ruins for decades or were only slowly demolished. Recovery from the destruction of the Second World War was a longer process, especially in economically weaker areas. The Ashton article also notes that she lost her mother at a young age and had a rather difficult relationship with her father throughout her life. In the smoky slow-burner “Dear Daddy,” she sings, Would you like to know what your daughter’s been doin, I listen to the Jazz and I blow them smoke rings […] Don’t ask me to come home / I’ve got a man on my own […] No wastin any time and you’d say ‘That’s good riddance’ / Don’t you understand I’m doing what you didn’t. It’s this mixture of defiance and self-determination that runs through many of her lyrics. Said song reveals an apparently strained family situation, suggesting that she may not have been able to rely on a grounding presence, a home. No knocking at your door no more, Daddy. Breaking out of the familial corset seems to her like an unfreedom, a kind of exile, a being cast out into a vacant world of myriad possibilities, where the rain is crying down for the broken hearts here in this town. In this sense of alienation, her lyrics often reveal a retreat into the safety of a romantic, sometimes mystical past. The lessons that I’ve had to learn / comatose as the world turns / maybe when the mist clears / I’ll see the towers of the city like the spires of utopian lands. Isn’t this feeling of not belonging, sometimes unconsciously, sometimes perhaps consciously, also an ongoing inner conflict with yourself and the world around you? Because you want to fit in, but ultimately can’t for idealistic, resolute reasons. You can hear it in many of her songs: a turbulent past that is, at the same time, a source of familiarity, a centre of warmth.

After eight years of trying to break through commercially, however, Jeanette seems increasingly disillusioned, disappointed, even angry. In particular, her last album, 1990’s Scale:1000 – a somewhat clunkily produced, Egyptian-themed art pop rough diamond – sounds in part like a swan song to a career that apparently never really wanted to be one. On the languid closer “Thunderstorms” she sings:

The dream fadeth I slip awake

through the dusty curtain

Gonna check the day

before I move

go through the door

before I fall

can’t face the street no more

Then, in the final, empowering verse, as if caught in a state of being torn back and forth, she continues to sing: I’m beyond the ways and the means of the destructive pillar / no move out of time will I absorb no isolated shiver. “I was surprised that they got the [Scale:1000] record out at all,” said Jim Irvin when I asked him what Jeanette might have done after 1990. “She seemed to be headed in a Syd Barrett direction, unfortunately.” Syd Barrett, the frail talent who burned out so quickly, caught in the grind of the music industry, lost in the spirals of fragile mental health and drug abuse. Of course, comparing a forgotten singer to one of the founding members of Pink Floyd might be a stretch in terms of cultural significance and artistic impact, but on a micro level, especially given her raw vocal gifts, the trajectory feels somewhat similar. On the jangly “Johnny” single, one of Jeanette’s last attempts at commercial success, she admits: I am seeking love like I seek razorblades […] And now I’m seeking substance like I seek of friends. The lines speak for themselves, possibly hinting at a growing malaise. As several contemporaries have pointed out, she wasn’t exactly the easiest person to work or communicate with. Towards the end, she appears to have developed a streak of paranoia, becoming increasingly convinced that everyone in the industry was trying to rip her off. Or so they say. The ambivalence of her musical career, her persona, can anyway be striking: In 1986, she recorded an incredibly haunting version of Donovan’s “Come Here My Love” for This Mortal Coil’s album Filigree and Shadow, which remained relatively obscure for years, as she had specifically requested to be credited only as “Jean” due to her dislike of cover versions. The contradiction between her desire for recognition and success, and the simultaneous reflex to reject it all: she wanted to make a name for herself, yes – but not at any cost. Over the course of her short career, the tone of her lyrics also seems to have shifted from the delicate tension of breezy melancholia to a noticeably more bitter, caustic note. It’s a strange mixture of resignation and anger hovering over this last phase; a persistent nervousness, a heightened sensitivity – the artist in her. More and more, she clashes with the harsh rhythm of the music business, with a kind of senseless fury, as if it were a personal attack. Just me and my cassette / big boys pull on my plug see / instead they look for trash with no talent. Commercial success never came, her records remained unnoticed. “After Survival Records stopped, Jean disappeared,” Irvin recalls. Where did her path lead? Into a bourgeois, conformist life? Ashton’s article mentions links to the scene around the Stonehenge Free Festival, that former anarchic gathering of counterculture, of drifters on the margins of society consisting of hippies, travellers, punks, mystics. And yet maybe it’s all nonsense – the speculation, the psychologising, the filling in of blanks, the pathos of it all. For isn’t it all there in her lyrics, the fragments and clues from which something like a life story could be pieced together, albeit in stylised form? Words that clearly needed to be sung. Words that never drowned in their melancholy, in the fault lines of the past, often revolving around the idea of escape, of a new beginning that might bring comfort. “The music is what she wanted us to know. And when nobody listened, she walked away,” Irvin concludes in Ashton’s article. What remains is a deep sense of wonder. Her raw, unique vocal talents, its emotional impact. The wondrous song “Leo”, and many other gems. It’s hard to shake the feeling that Jeanette was something of a lost soul, a defiant spirit that flared up briefly before vanishing into obscurity. The rest may remain closed, belonging to a memory that is all the more formless and fleeting. And the fullness of time won’t leave a trace.