R

eleased on screens in 1992, this film by Canadian director Guy Maddin opens up a fairy tale book for adults. Set against the idyllic backdrop of a snowy mountain village populated by a cast of peculiar inhabitants, it takes us down a rabbit hole of human abysses. Being both a homage and a parody of the kitschy genre of the Heimatfilm, Careful (Lawinen über Tolzbad) thus accommodates both the wondrous and the strangely familiar. As a result, it brought me to reminisce about my childhood days around the spa town of Bad Tölz in Upper Bavaria, whose surrounding mountains and valleys still loom large in my memories to this day. Its German subtitle, which with “Tolzbad” clearly contains a reference to said childhood place, was the reason that drew my attention to the film. Although the name refers to a fictitious Alpine village and plays into the often clichéd notion of Alpine culture and way of life, its association with this little town is clearly benevolent. Yet, the Alpine idyll is deceiving: in Careful the viewer is shown a slumbering monster behind the picturesque landscape – the fear of the destructive snow avalanche. From it, a frightening dominion is born, which grips the villagers at their core; their impending fate transforms the beautiful sugar-coated, familiar world below the mountain into a snow globe that one day will be shaken by the hand of a sinister god.

In a balancing act between winter fairy tale and Moloch, Maddin allows us to glimpse in his Tolzbad microcosm with unbridled, flourishing imagination as he unabashedly embellishes and caricatures. Even more is discernable when the everyday life of the villagers takes its course; it gets further elaborated and lovably distorted and fantasized. No faces battered by the hard work of farming, no torn rags or sweaty stable boys in lederhosen – instead, fairytale-like, flowery costumes and doll-like make-up are meant to complete the fantasy world. Secret love affairs and feverish desires blend into the twilight of the lanterns. Thus, a Shakespearean love tragedy unfolds on the screen, as a sensory-deceptive and unreal daydream that turns the village’s daily activities into an almost psychedelic spectacle.

I believe that Ludwig II, former King of Bavaria, would have enjoyed this film, as he, too, escaped into fantasies of rosy-cheeked princes in flowing robes, mythical depictions, and over-stylized, saccharine romanticism. He had entire halls and his own grotto created to satisfy his yearnings for his Wagnerian mythological world. And even far away from that, he liked to retreat to the quiet mountains of the Bavarian Alps. Maddin seems to take a cue from this enigmatic “Fairy Tale King” and his laudanum-drenched phantasms.

In kinship with those surreal castles in the air, dream scenarios rise to the surface here, adoringly reminiscent of early film history’s expressionistic works by F.W. Murnau or Fritz Lang from the 1920s. Almost every scene breathes the spirit of these past art movements: sometimes monochromatic, sometimes with typical black-and-white subheadings – even the visual style of the silent film era is stylistically evoked and emulated. With slapstick antics, Maddin also knows how to inject an eminently thoughtful dose of “absurdist comedy.” Silly scenes keep breaking through – unexpected, inappropriate, wonderfully funny. One image that stands out at the beginning is the appearance of the Alphorn players at the Tolzbad “Spring Concert”: young men made up in an over-powdered androgynous façon, adorned with flowers, honk on Alphorns apparently glued together from paper-mâché as their lullaby echoes like a hymn to the drunken, dreamlike atmosphere that pervades the entire film. Under the smitten gaze of his sweetheart, one of the horn players amuses the audience with his off-kilter tunes. Nothing here is ever enduringly tranquil, beautiful, or flawless – the eccentric, quirky, and imperfect puncture such moments of seemingly perfect images, mocking the tidy and mundane superficiality.

Like a bottomless prop box overflowing with all sorts of curiosities, grotesque details can be found everywhere in the film’s backgrounds: a paper-mâché goat’s head serving as wall decor, mimicking the typical rural decoration of hunting trophies; a worn cloth duck that serves as a cuckoo clock, or the waterfall that produces soap bubbles in the roaring rush of the water. In addition to dramatic or cheerful orchestral renditions, the music and sound effects consist mostly of a kind of “white noise,” which shows itself in dynamic variation, sometimes subtle, sometimes overpowering. Perhaps some may hear a snowstorm in it, perhaps a sonic depiction of inner turmoil – the constant upheaval in the film’s essence. Or maybe some even perceive the “white noise” as a calming, soothing factor.

Silhouettes of the mountain world often seem like people wrapped in cloth, curled up into peaks and shadowy rock formations. The film’s scenario literally seems to be living, and amidst the veiled, deliberately vague depictions, the viewer’s eyes are probably meant to be initiated into a hallucinatory shadow play. Geographical conditions are freely and boldly interpreted, like the Eigerwand always being within reach and typical Bavarian first names are twisted to the heart’s content – distortions that adorn the film with charming inconsistencies.

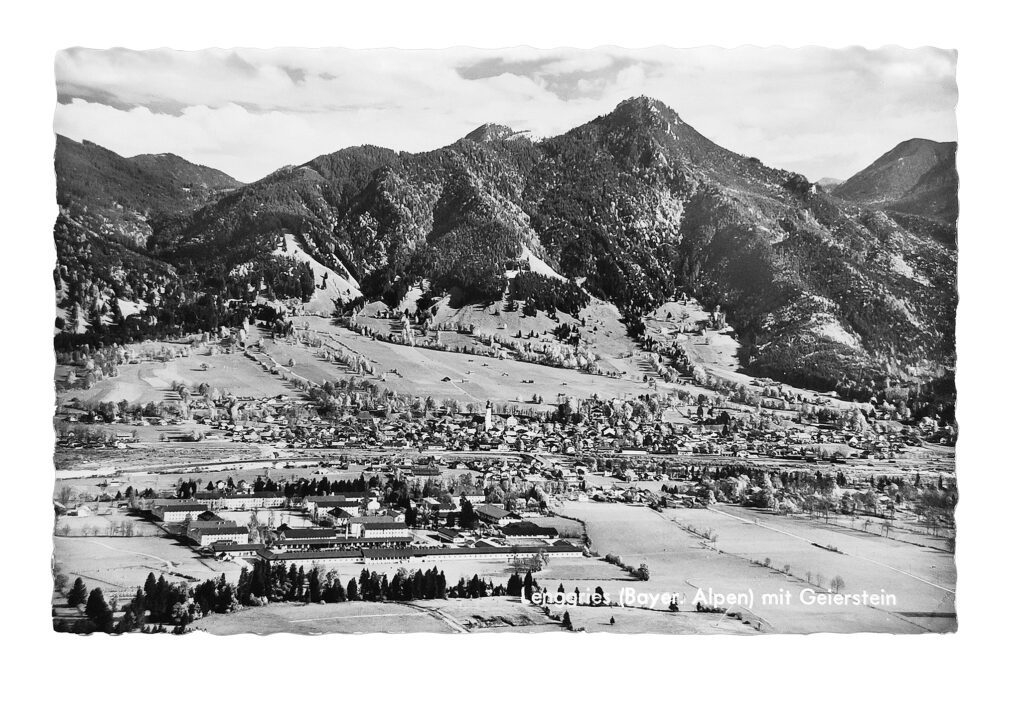

The Geierstein, located in the region of Bad Tölz, could undoubtedly have served as a real-life model for this film. In my childhood perception it always had a somewhat gloomy appearance, which fuelled my imagination and always triggered a certain inexplicable creepiness in me. Darkly imbued with its effect, it repeatedly appeared in my dreams. There are countless scary stories from the area, but no significant myths, legends, or such an aura are attributed to the Geierstein. For some unknown reason, my childhood imagination had picked out and conjured up an eerie spell again and again. It can be said with certainty that such a mountain in close proximity has certainly not played an insignificant role as a real danger for the region in long, snowy winters.

If one goes south from Bad Tölz deep into the mountains, one reaches the extraordinarily remote village of Jachenau. It is said that, due to the location amidst special mountain formations, the people there are subjected to an unnaturally long, sometimes complete absence of sunlight, as the rock formations prevent the already low sun from shining in. Some farms are even said to remain in the shade all year round. The locals in the surrounding areas call them less mockingly and more pityingly Schattenseitler. Likewise, livestock is reportedly affected by the lack of light, with the “shadow farms” struggling with unfavourable conditions for agriculture and depressed spirits. Although, as I later found out, this phenomenon is quite common in the Alpine region and not particularly unique, it captured my imagination at the time, making me think of gloomy figures pursuing a lonely, equally dreary life in the shadow of the mountain range, just as dictated by the surroundings. Bent with bitterness and resentment, devoid of happiness, so I imagined, they would dress in dark garments to match their mood in order to disappear into the shadows. As a child, I sometimes worried about the locals and wondered how they might cope with this infinite darkness, and in my imagination they were always looking towards the peaks with sinister, fearful faces, cursing them forever.

Here, too, a parallel can be drawn with the elemental force that dominates the film, exerting its influence on humans and animals alike. Similarly, Jachenau, an ideal image of magnificent nature and country life, embodies an in-between world of discomfort and unease that does not fit into the otherwise enchanting surroundings. This had always fascinated me in an eerie way.

In Careful, pretty, colourful images and idyllic snowfall are illusory as well. It quickly becomes clear that something is wrong: a dog’s bark fades pitifully, in the barn cows stand in eerie silence, and the night watchman, who usually makes his evening rounds with a loud call, with horn and trumpet, creeps from door to door on silent soles like a ghost, whispering softly to urge people to sleep.

Careful, Tolzbad – careful, careful!

The dreaded death by avalanche and the looming destruction of the village cause the residents to fall into an excessive obsession with caution and commandments, just so as not to wake the sleeping monster. They reprimand each other for their transgressions, admonish and denounce. In a way, they are slaves to their god, so to speak, whose wrath could be unleashed at any time through their sinful deeds. This must be prevented at all costs. No sound, no word must reach the watchful mountain. From now on, all residents, young and old, and even the cattle must exist as quietly as possible, as any carelessness could trigger disaster. From this forced, silent way of life, a parallel universe emerges, where self-control is practised and any kind of emotion must be painfully suppressed and hidden. Natural processes now follow strict discipline and order. Only in small, protected spaces, the so-called “mountain ganglia”, can people speak, laugh or sing to some extent.

A mad delusion, believing that safety can be achieved in this way, for the village community is like a steam boiler in the invisible prison of regulations. It becomes impossible at a later point to say which pressure will be released first and whether the oppressed feelings and renunciation of the noise of life will not be the actual disaster. Throughout the film, eroticism is also presented as the driving force, particularly emerging under the weight of repression, thriving and taking on increasingly bizarre forms – even corrupting individuals. Incestuous relationships repeatedly appear and haunt individuals. Sigmund Freud would undoubtedly have been eager to analyse these constellations in his Oedipus conflict. And as the inhabitants of Tolzbad tame themselves outwardly, their innermost selves are stirred. This constant conflict has its consequences: all of their fatal, malicious traits emerge. Anger and despair seek their way outwards. Immoral behaviour and crimes, self-mutilation, and even a desire for death now dominate the mood in Tolzbad. The dams of restraint and regulation can no longer withstand the growing anger and the corruption that grows into a monster.

Although the film has not achieved any significant international success or attention, it stands for the unbroken and constant entanglement of the fantastic in movies; a fever dream of Maddin’s that weaves the unironic glorification of kitsch into a human social dilemma, remaining as relevant as ever. A silent scream into the seemingly immovable mountain walls of reality, the echo of which is mercilessly thrown back and preserved in Maddin’s snow globe.

Careful is a bizarre, eccentric fairy tale – a unique gem, not in spite of, but precisely because of its numerous references to existing film styles.

——–

This text was published in LÄRM – Issue #3, Nostalgia and Reason

All filmstills © The Canada Council/Guy Maddin