by Valeria Calderoni

Dear Generation Y,

I am addressing you directly because I believe we share more than only the epithet of “millennials”, which sounds almost derogatory at this point due to the many times it has been used to illustrate some of our worst features. Maybe we share the same comfortable and privileged background, where all our fundamental needs are satisfied at all times. Despite this, you might also share with me a latent feeling of inadequacy, alienation, dissatisfaction, or guilt. These feelings could be sensed through a certain kind of music and movies already in the early 90ies, before we could fully understand them through our own experience. In my opinion, the filmmaker that best managed to encapsulate them in his work is Gregg Araki, one of the most underrated true auteurs of the last 30 years. Araki started making movies in the late 80ies, reached peak underground popularity around 2004 with Mysterious Skin (which features some of the most disturbing male rape and child abuse scenes in the history of cinema as far as I’ve seen) and released a few more movies before switching to TV series for good in 2016. An absolute gender bender, Araki explored a wide range of movie genres to show life from the point of view of queer, gender-fluid teens in search of their identity. The themes of alienation and inadequacy run like a thread through his whole work, but his 1995 movie The Doom Generation offers us the most interesting case in point.

Not only because of the “nihilistic, immoral” feel to it that scandalized most of the press; not only because of the somber atmospheres conjured up by the soundtrack (put together by 4AD label co-owner Ivo Watts-Russell among others, and featuring Nine Inch Nails, Front 242, Coil, Love & Rockets, Slowdive, Cocteau Twins, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Aphex Twin, Skinny Puppy and Medicine to name a few); not only because of the protagonists being three sexy young actors destined for the Olympus of 90ies countercultural teen idols (Rose Mc Gowan, James Duval and Johnathon Schaech), but because it speaks of us on many different levels.

I’m not alone in holding this opinion: despite it being badly received by the mainstream press at the time, during the twenty-five years since its release the movie became the subject of ecstatic reviews, interviews and books describing it as an “iconic and subversive portrait” of futility and alienation that marries Araki’s “Godardian cinematic style with industrial music”, a “road movie for the AIDS generation” that “captures the cultural apathy of the present”. Film scholars and critics alike seem to recognize the ability of the film to offer a sharp and poetic glimpse into our generation’s characteristic brand of “existential struggles”. In one sentence:

We are “The Doom Generation”

First of all, we share a collective unanswered question, among other things: are we or aren’t we The Doom Generation? Those who grew up “knowing they will see the end of the world”, as Jordan (James Duval), one of the protagonists of The Doom Generation, asks at one point in the movie? There’s definitely some truth behind this seemingly melodramatic question. Nowadays many would at least agree that the future doesn’t look especially promising for a variety of obvious reasons (climate change, the newfound vigor of populism, racism and homophobia, the crisis of democracy, and so on). Even before the latest developments, we had realized that things weren’t quite going the way we had expected, or maybe they were going exactly the way we had feared they would. The world turned out to be much more complex than we thought, and it’s not going to get any easier.

We should have known that, but we were not prepared. When The Doom Generation (and other “anti-coming of age” movies filled with existential dread) came out, schools, parents, and the media – especially TV, of course – were still busy telling teenagers and kids of the wealthy western world that they could be “everything they wanted to be when they grew up” – as long as they studied hard in school, never broke written and unwritten rules, and bought the right products. The oldest among us entered adult life when the elaborate system of deception built by capitalism to promote itself as the only viable option started to manifest its faults even among the members of the most comfortable social classes – and it became clear that the path laid down for us was paved with wrong assumptions, wild guesses and wishful thinking.

I’m not here to point fingers, but rather to understand and move on. We can’t really blame our parents and teachers for telling us that by doing well in school we would “make it” in life. At the time it was true – but now education no longer makes a difference on its own. Resilience, hard work and discipline in particular make a great deal of difference, but we haven’t got plenty of that stuff. When it comes to our parents, I’m always inclined to think that they did their best and they gave us everything they could, but it was probably way too much. They worked hard, but in most cases we never had to.

An inevitable culprit is TV; when we grew up, kids used to watch it a lot more than would nowadays be considered healthy. I recently rewatched a lot of movies from the 90ies and noticed how heavily and frequently TV was embedded in them, often to be mocked or revealed as a corrupting tool of mass control: Natural Born Killers, Reality Bites and even Twin Peaks are some of the most explicit examples. We could definitely say worse things about the internet now, but in the late 90ies it was still a wonderful place filled with well-meaning nerds, and very few could foresee its future impact on society (to quote David Bowie in 1999: “I think we’re actually on the cusp of something both exhilarating and terrifying”).

If you ask me, I won’t hesitate for one second in putting religion to the stand as well. Not only because of all the usual misdeeds of Christianity, including its role in securing and sealing the triumph of capitalism, but also because it induced us to take full accountability for things we’re not even responsible for – and especially because it encouraged us to dwell in our sense of guilt instead of teaching us to love ourselves the way we are, in order to be able to love our fellow man.

As our living conditions improved, we kept expanding our definition of “successful”, but we never worked on revising it as a whole. What does it mean to be “successful” anyway? Does it mean making as much money as possible – or at least being able to support ourselves – while also successfully “doing what you love” for a living, honoring the time spent getting an expensive education, setting up a family and ultimately being happy, happy, happy?

“Are you happy”, to quote Hord of Occvlta? Me neither. I feel more like Sisyphus; Camus said that “one must imagine Sisyphus happy” as he drags his humongous stone up that mountain every day for eternity, so what’s the big deal one could say? We might have never been burdened with a magnitude of weight comparable to Sisyphus’ boulder in our lives, but we are juggling way too many small exasperating “stones” of responsibility to be able to feel that “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart”. We can’t start going anywhere if we don’t let some of those stones drop to the ground first.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising that we took refuge in the escapism of drug-infused bliss, self-obsession or social media, or that we started wearing our passions and talents like blinders to avoid looking at the grim landscape of our present and future. The “cultural apathy of the present” works as a comfortable shelter from the state of alienation we still find ourselves in today. That’s why The Doom Generation is one of those movies that still speak to us: it’s a road trip to nowhere, anywhere, as long as it’s far away from the inadequacy and guilt eating us up since we started being conscious of our own situation.

Apathy For The Devil

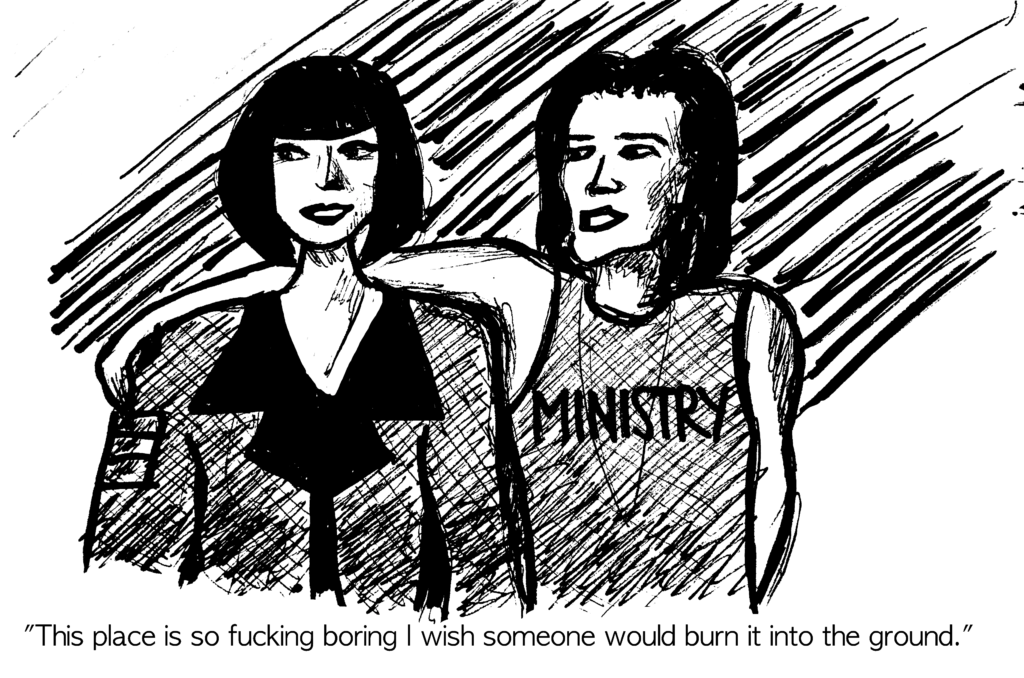

The film opens inside a club in L.A., where a bored Amy (Rose McGowan) is trying to light her cigarette but can’t find her “skull lighter”. She proceeds to rebuff a man twice her size that approaches her asking for drugs, by offering him a couple of eloquent expressions from her vast array of multifaceted, long-forgotten 90ies slang terms (one of my favorites: “Mellowize thyself, fishwich!”).

Everyone in the club is dancing to Heresy by Nine Inch Nails: “God is Dead/ And no one cares/ If there is a hell/ I’ll see you there”. The song is followed by a remix of Religion from EBM kings Front 242, a wonderfully apocalyptic cyberpunk track from their 1993 album 06:21:03:11 Up Evil that goes: “You see, the sin is in me/ When will it stop unfolding/ When will I ever be face to face/ With the devil in me?”.

The soundtrack seems to have been carefully selected to work as an ominous, profetic guide to the movie, because “the devil” is precisely what Amy and her boyfriend Jordan (James Duval) end up facing after leaving the club and trying to have sex in a parking lot. Their attempt to lose their virginity fails because Jordan is afraid of catching AIDS; shortly after, a complete stranger named Xavier is pushed over their windshield by some very angry dudes who are attacking him, so he enters the car and urges Amy to hit the gas.

Xavier (Johnathon Schaech) soon becomes their guide through an indolent journey of self-discovery, as the three embark on a directionless trip to escape their enemies and their fate, which is invariably up against their (lack of) will. If anything can go wrong for them it does, and Xavier is the only one among them who seems well-equipped enough to address the challenges they face as they continue to bump across omnipresent flocks of grotesque, aggressive strangers who despise them and want to kill them for one reason or another.

As Kylo-Patrick R. Hart pointed out in his 2010 book on Gregg Araki titled Images For A Generation Doomed, the violence is often way too campy and funny to be the point of the movie. What’s often overlooked, however, is that love is never diminished or caricatured: it’s always dreamy, wholehearted, eager and real. There’s always shoegaze music in the air when Amy and Jordan have sex; he loves her unconditionally and she calls him “the bright red cherry on top of my sundae”, the only endearing metaphor in her lexicon filled with colorful insults thrown at everyone else she meets. Araki’s press kit described the bond that forms between Jordan, Amy and Xavier as “a triangle of love, sex and desperation too pure for this world” (courtesy of film critic Roger Ebert, who mocked this and other passages from the press kit in his resentful review of the movie, to which he gave zero stars).

Both Jordan and Amy feel attracted to Xavier from the beginning; they gravitate towards his unrestrained sexual drive and benefit from his quick and sharp survival skills despite their initial reservations. Why is only Xavier able to react and available to take responsibility for his actions? Maybe because he is one hundred percent guilt-free. “Guilt is for old married couples”, he tells Amy after the two had sex for the first time, and “life is but a dream”, he sings while taking a bath.

Amy’s conclusion is that he must be the Devil: but the Devil belongs to the same system of values as God does, as most of us “Lucifer’s friends” realized by now. By building a philosophy on embracing the opposite of the prescriptions listed in the Bible, the Church of Satan didn’t manage to prove Christianity obsolete. To pay any attention to LaVey, one must have had some interest in what our self-styled representatives of God on Earth had to say in the first place. I treasured my copy of The Satanic Bible when I discovered it at sixteen after “escaping” a strict religious upbringing, but I lost track of it many years ago: that “phase” was necessary for me, until at some point it wasn’t anymore. I think we can’t really break away from any system of values only by belligerently invoking the opposite of what it prescribes, because we’d still be measuring ourselves against it.

That’s something even Charles Manson, the guiltless villain we most often equate with the Devil, warned us against. First Dark Ride, a song by Coil included in The Doom Generation soundtrack, features a sample from Manson’s 1988 interview with Geraldo Rivera in Quentin State Prison, where he famously said:

“OK, I’ll play, there’s no game I can’t play… I’ll be the Devil. Your courtrooms have convicted me for being Jesus Christ in one courtroom, and then in the other courtroom you convicted me for being the Devil… Do you need someone like that in your world? That’s your judgement now; the judgement you make on this mirror man you gotta carry… I am God and I’ve killed everyone, now what? It does not improve your issue any. …

…What you are doing is you’re creating a legend, you are creating a beast, you are creating whatever you judge yourselves with into the word Manson, and that’s not me at all, man!…”

The 99 Problems of the 99 Percent are One

In the last century, slowly but surely, we managed to “kill God” under many respects, but we haven’t really opened our hearts to a valid alternative source of enlightenment yet. Those who are successful think they don’t need it; those who aren’t rarely look any further than the particular issue they have at heart. One can only be either with us or against us on any issue – veganism, climate activism, feminism, you name it. We are harsh judges of ourselves and others, and our radicalist sectarian approach to the dismantling of outdated values prevents us from seeing that our different problems, traumas and wishes are connected in many ways. This works in favor of our common enemy: we’re still playing by its individualist rules.

Spoiler alert: in The Doom Generation, our favorite “band of outsiders” are, unsurprisingly, headed for a violent epilogue. Amy, Jordan and Xavier are tracked down by a bunch of homophobic Nazis to the abandoned warehouse where they are hiding and engaging in their first passionate, liberating act of collective sex. The Nazis quite literally “put our their fire” right before Jordan and Xavier can continue enjoying their intimacy without Amy, and proceed to brutally torture and rape them in the goriest ways imaginable. Jordan, a sweet and dreamy creature filled with wonder and love, but also loaded with fears and self-doubt, pays the highest price; or does he? In any case, they were doomed; their trip ended before their journey towards boundless, universal love was complete, but the same doesn’t have to happen to us.